A defence of the gotcha question

Not knowing a number under pressure doesn't disqualify you from Government. But it is interesting.

Press conferences are terrifying places. I’ve stood in front of the cameras to give people a white balance enough times to know that just the glare of that many lights and eyes on you are enough to dazzle your brain - let alone the idea of ten reporters all shouting demanding questions at you, each one of which could potentially be cut into a clip seen by millions of people. The only way to get better at them is to practice, and even after countless hours it’s still easy to make a mistake that gets pounced on.

But there are ways of getting out of bad spots in a press conference. You can try to move away from a rough line of questioning by switching your attention to another reporter. You can also provide bad and awkward TV - spending a long time constructing a boring sentence which kinds of addresses the question but doesn’t answer it. TV and radio shows are pressed for time - if you make the answer dull enough they may not run anything at all.

This is not an option you have while being interviewed live. Tens of thousands of people are listening or watching you live and many more will go back on replay. Both the question and your answer - or any silence surrounding it - will be heard. This can make an inability to answer a questions properly far more excruciating.

Yesterday morning, super-star RNZ interviewer Guyon Espiner sat down for the weekly slot with National leader Christopher Luxon and got him with a classic gotcha: Luxon was unable to say - even roughly - how much a single person received from superannuation. (Instead he could name how much they might save from National’s proposed tax cuts.) Cue uncomfortable headline:

For the uninitiated, a “gotcha” is the (somewhat derogatory) term for a certain type of question journalists use to test the knowledge of those in or seeking power. Instead of asking for their opinion or policy prescription on something, you ask them if they can tell you what the rate of unemployment is, or how much a bottle of milk costs. If they answer correctly it’s a non-story, but if they slip up - particularly if they slip up terribly or just can’t even get anywhere near, it can become a real “talking point”.

The most famous gotcha of recent times concerned Anthony Albanese at the Australian federal election earlier this year. The then-opposition leader could not name either the official cash rate or the unemployment figure when asked. This dominated coverage for a few weeks, as reporters attempted to recreate the moment - which got ridiculous. Greens leader Adam Bandt earned serious praise from responding “Google it, mate” when asked about the Wage Price Index - a far more obscure figure than the unemployment rate.

Bandt’s point was well-made. It’s okay to not know every single type of economic indicator at all times, particularly when you can, in fact, “google it”.

But I think this kind of gotcha questioning has a real place in our political landscape.

Now, for the supermarket price questions, you aren’t really testing if an MP is in touch with the common people, you are testing whether they have a good media staffer providing a decent briefing book. I had great sympathy for then-National leader Judith Collin when she didn’t know what the price of a 1kg block of cheese was during the 2020 campaign, because buying a 1kg block of cheese in the middle of an election campaign would be a stupid thing to do, as it would go mouldy long before you would have a chance to eat all of it. It didn’t make me think she was out of touch, it made me think she needed a better briefing book - or just to study hers more.

Yet I think the process of study that MPs have to undergo to be prepared for these supermarket-type questions is probably a good one. And it is a process of study: A former National Party staffer mentioned to me on Twitter today the briefing book in 2017 was about two inches thick. There is nothing like seeing how prices actually impact people on the ground - a lesson journalists should consider as well as MPs.

As a personal example: I don’t own a home, so mortgage rates are fairly abstract to me, meaning that when I was thinking about “inflation” earlier this year I was generally thought about how much more it cost me to go to the supermarket every week. But while researching a story I delved into the numbers to work out just how much rising interest rates would affect someone on the median wage with the median amount of their mortgage left to pay off - and it was huge! It totally turned around the issue for me, actually making me feel sorry for those who were lucky enough to own their own home. I had known in the abstract that these costs were rising, but actually seeing the cash amount it had gone up in just a year made it far more real.

Politicians doing this with everyday essentials and with key prices every week or so is probably a net good for their understanding of the economic reality of everyday Kiwis, far away from the austere tables of Treasury briefings.

I’d put Luxon’s superannuation gaffe into this camp. It’s reasonable that he doesn’t know the exact amount - he could probably receive the super every week and not notice the extra cash - but it would make him a better politician to have that kind of figure bouncing around his head, especially given he is dead-set on raising the age of eligibility.

For macroeconomic indicators like the unemployment rate I genuinely think those leading or seeking to lead the country should be across them. This doesn’t mean everyone should have to name the GDP per capita growth rate of the last decade down to two or three decimal places, but I think if someone asks you what the unemployment rate is and you get it wrong by 1.4% as Albanese did that speaks to your actual understanding of the economy.

That doesn’t mean not knowing a number or fact is disqualifying, but it is certainly interesting. Jacinda Ardern, for example, couldn’t confidently name the articles of the Treaty of Waitangi when asked. This doesn’t mean she should never be allowed to speak on Treaty issues, but it does speak to her general headspace at that point - like many Kiwis she had a vague understanding of the Treaty, not a specific one. (Ardern also made a silly mistake at one point concerning the crown accounts and GDP. This was not quite a gotcha question though, more a strange mistake.)

This is a modest defence of the gotcha question. I think they should be a fairly rare occurrence, not something to whip out at every interview. But they have a proper time and place.

The entrenchment mess

I’m late to this because I was in Budapest all weekend, but it is good news that the Government looks set to reverse its decision to entrench a section of the Three Waters bill with just 60% of Parliament.

We save entrenchment for electoral law for a reason. It’s understandable that people have very strong feelings about the privatisation of water, but here is a small list of other things that are not entrenched:

The right to free expression

The right to a fair trial

The right to a public education

It really only makes sense for electoral law, where binding a future Parliament is the right thing to do. If you want to change that - which is fair enough! - do it properly, not via an SOP.

Recommended reading

Jo Moir on the chaos behind the entrenchment mess.

Kirsty Johnston on the horrific situation quite a few migrant workers end up in, held hostage to their sponsors.

Bill Bishop from Sinocism on why the protests in China are very interesting but probably won’t result in serious change.

Helen Sullivan on Micronesia, where an island was artificially built by humans like 3000 years ago (!)

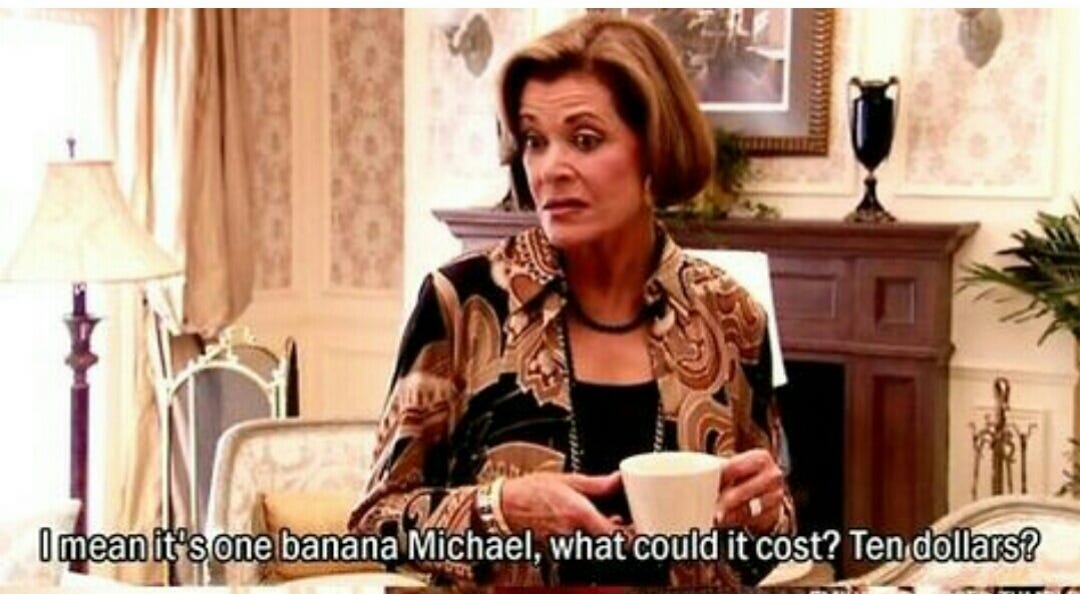

This meme:

Then there are gotcha questions like the one testing whether a leader of the opposition remembered a letter to a constituent sent several years previously.

The PM's knowledge of Te Tiriti is detailed. She might have been unclear whether the question was about the articles or the principles, and which version. The principles of the ToW we learned a few years ago of partnership participation and protection are different from Te Tiriti principles. So citing the specific articles of the English translation is different from understanding its complexity (which she does).