MPI think climate change will make NZ richer. MfE disagrees.

An intriguing look into how the deep state thinks about climate change.

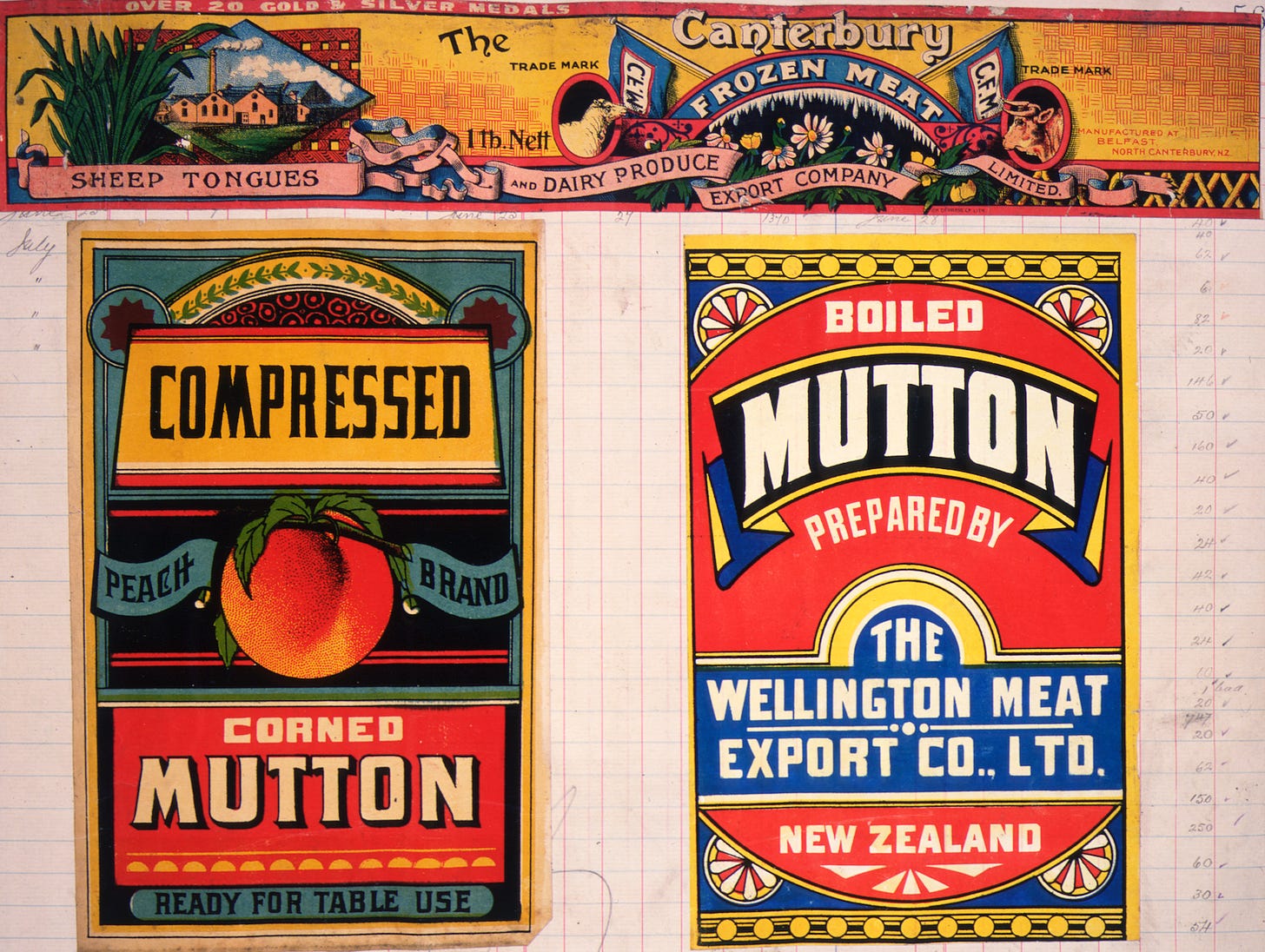

New Zealand has a long history of exporting protein.

We are very good at turning our plentiful rain, land, and technical expertise into exportable animal products, whether that be sheep-meat for London in the 1880s or milk powder for Shanghai in the 2010s1. It is not our entire economy but it is the backbone of our export economy - dairy and meat made up about 45% of our exports last year. While the benefits of this export boom are far from equally distributed, we would likely all be poorer without it.

Understandably, governments over the years have had a deep and abiding interest in the success of this protein industry. When the “rain” section of the protein-tripod isn’t quite there it delivers subsidies for irrigation, even where that irrigation helped destroy freshwater ecosystems. When the Government does regulate the giant of Fonterra, which had revenue last year equal to about 8% of our entire GDP, it describes this regulation as a “deal” - something that you usually see between two similarly-powerful entities, not a company and a Government. Trade pacts with market access for agricultural products are a huge part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s workload, and the separate Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) also have their own trade unit.

It is MPI that this newsletter is about.

MPI: Champion and regulator

MPI is a big beast of the New Zealand public service. It has three and a half thousand staff on an average salary of $101k. Its main building exists just a few steps up The Terrace from Treasury and the Reserve Bank. I can’t think of a single time that the Minister for Primary Industries has not been in Cabinet.

And yet this big beast operates in a somewhat ambiguous position. In some areas, they are undoubtedly the regulator - see fisheries, animal welfare, and food safety. But in others they are industry cheerleaders, championing New Zealand’s agricultural industry as much as governing it.

This isn’t a secret. MPI had a stated goal in the mid-2010s of doubling NZ food exports by 2025. The most recent annual report states MPI’s purpose to “…protect the food and fibre sector from pests and diseases and support it to build a more prosperous and sustainable future for all New Zealanders” (emphasis mine.) The first line from the director general is in the same vein, only more so - he brags about how MPI have helped exports grow to a record $53.1b. Staff are occasionally seconded to private sector agricultural organisations.

This ambiguity on regulation is often down to working out what is MPI’s role and what is the role of the Ministry for the Environment (MfE). MfE have about a quarter of the staff, but with no competing role as an industry champion are often on the pointy end of regulating farming - for example by managing the freshwater reforms, or leading consultation on the fraught proposal to in some way tax agricultural emissions2.

Climate change is the biggest policy issue facing our primary industries in the years to come. Agriculture is both our biggest emitter and biggest carbon sink, and is extremely exposed to weather events and regulation. Yet it seems that another agency are doing much of the work on that regulation.

But that doesn’t mean MPI doesn’t have a view on climate change. As I found when poking around their Long Term Insight Briefing.

How MPI sees the world in 2050

These far-sighted briefings are the result of Chris Hipkins’ public sector reforms he made before becoming Prime Minister, and ask departments to periodically issue advice and analysis on a very long-term issue. This is something that Treasury has traditionally done for the Government’s books but other agencies have not, instead restricting their analytic skills to the immediate or near future

Agencies have some freedom in what topics they focus on, and MPI decided to look at “The Future of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Food Sector: Exploring global demand opportunities in the year 2050”. This briefing was released in April to little fanfare - you can read it here.

As you would expect, it is impossible to write such a document without considering climate change. And the authors did - they just seemed to think it would help New Zealand. On page 18 beside a stock image of a smiling toddler the authors write:

Our existing export food markets are in a very good position. While we will need to maintain and build our own resilience, New Zealand should benefit from growing demand and higher prices that may arise from climate disruption and an increasing world population. (Emphasis mine.)

Elsewhere in the paper you can find the justification for this remark - basically the reduction in supply for other countries because of climate events will result in overall food price hikes, which are good for New Zealand producers.

Looking out to 2050, a study by the Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit (AERU) indicated that, while there may be more regular and more impactful and distressing shocks to different parts of the food sector and different regions, more frequent climate events are unlikely to cause major overall impact on our food export revenues. This is because with more frequent and widespread events worldwide, New Zealand food export revenues are likely to increase overall relative to other countries as revenues benefit from higher prices resulting from global reduction in supply. (Emphasis mine.)

This is quite a stark way to put it, especially just a few months after the climate-change-amplified Cyclone Gabrielle did somewhere between $500m and $1b in damage to the agriculture sector. But it is true that other parts of the world may fare worse: Europe is currently on fire, and the repeated droughts are sending food prices up around the world as staples like olive oil are largely produced there. New Zealand creates enough food every year to feed itself eight times over, so it is likely that we will have an easier time of increased crop failures than other countries that need to import much of their food.

MPI cited a study from Lincoln University’s Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit to make this finding. I asked and received a copy of this study from the university, and it largely backs MPI’s conclusion. From the executive summary:

The results indicate that in a world experiencing frequent and widespread extreme events, New Zealand producers may benefit from the global reductions in supply and resulting higher prices, and experience higher producer revenue than in a world with less frequent extreme events.

These results are based on a detailed economic model and an assumption that there are more frequent and extreme weather events both in New Zealand and around the world. The authors are careful to note that consumers facing these higher prices might not be so happy and that this would increase existing inequalities.

From what I can tell, regulatory responses to climate change were not considered in the modelling. So if the EU decides it will slap a tariff on any milk created in a country that doesn’t tax agricultural emissions that would change this scenario. Also not considered is the potential for a massive global shift to non-animal proteins, whether by regulatory force or consumer preference. To be fair, this stuff is hard to model.

My read of this conclusion from MPI - that the human misery of extreme weather events around the world would be a net positive for New Zealand thanks to the higher prices foreigners would have to pay - seemed a touch evil, so I asked the agency if that was a fair way to read the paper.

Chris Kerr, Director Strategy and Insights, told me via the MPI press team that: “It would be an oversimplification to say that climate change will be a ‘net positive’ and that is not the intention of this report.”

Later in his response, which also discussed Cyclone Gabrielle, he reiterates the points made in the paper, but notes these are from an “economic perspective”.

“The LTIB references research by Lincoln University experts that looked at the effects of climate change on production output and what that might mean for the sector economically. That report found agricultural output could drop, creating supply constraints, which from an economic perspective may create stronger prices.”

What MfE thinks

Interestingly, the other side of that regulatory ambiguity has also produced a Long Term Insight Briefing.

In MfE’s briefing, the effects of climate change are unambiguously Not Good for our agricultural sector.

Climatic changes in some parts of the country may have benefits for agriculture, such as warming temperatures extending growing seasons (Ausseil et al, 2019b). However, any benefits will be far outweighed by negative effects, such as increased rainfall variability, droughts and water shortages, and heat stress to livestock (Ausseil et al, 2019b; Hendy et al, 2018). This will cause major losses to farming operations and negatively affect the wider environment (MfE, 2020a)

MfE also look at consumer behaviour - but are more alive to the possibility of a big push away from emissions-intensive animal proteins.

Alternative protein products could be one of multiple options with regards to concerns about the ethics and sustainability of intensive animal farming. While only a small portion of the global market – estimated at 2 per cent in 2020 – this is expected to rise to around 11 per cent by 2035, as price and taste become more comparable to traditional meat and dairy products (Morach et al, 2021). How Aotearoa New Zealand meat and dairy producers respond to these shifts can have a significant effect on farming land (Te Puna Whakaaronui, 2022).

They also discuss “unequal crop yields” and how these will effect commodity prices, but note that this might change trade policy too.

With middle classes growing and emerging around the world, demand for Aotearoa New Zealand’s primary sector products is likely to stay strong over the next decade and beyond (MPI, 2019a). Changes in dietary preferences and unequal crop-yield changes will also likely drive changes in commodity prices and trade policies, affecting the agricultural sector (MfE and Stats NZ, 2022)

Much like MPI cite a Lincoln University study, MfE cite the triennial Environment Aotearoa report they produce with Statistics New Zealand, which has this to say about agriculture and climate.

The agricultural sector relies heavily on rainfall and is particularly vulnerable to the extremes of both high and low rainfall. As farmland is often located on fertile floodplains it is particularly exposed to the risk of flooding (Craig et al, 2021), while water availability during drought events also poses a high risk.

Drought events can have even greater impacts on the primary sector than floods. Droughts cause the soil to dry out, and can lead to the loss of almost all of a farm’s profits (Bell et al, 2021)

[…]

Throughout the world farmers are shown to be particularly susceptible to the mental health risks associated with drought (Cianconi et al, 2020). Following Australia’s decade-long drought ending in 2012, studies found an increase in anxiety, depression, and potentially suicide in rural communities.

[….]

Warming temperatures may pose serious risks for the health of livestock. This can be directly through heat stress (Ausseil et al, 2019), and indirectly through potential increases in existing diseases (such as facial eczema), and through more severe microbial and parasite infections (Lake et al, 2018). Warmer temperatures may be favourable to insect pests, increasing damage to crops and plantation forestry (MPI, 2015).

In other words, a picture that is far more grim than the one MPI imagines.

Why this matters

Working out how New Zealand can continue to be prosperous while responding to climate change is the great policy question of the next decade and more.

Responding can mean different things to different people.

For some who think our impact is so small we might as well give up “responding” will mean working out how to live in a dramatically warming planet. They will point to the fact New Zealand’s emissions are a fraction of a percent of the global whole, and express doubt about the possibility of carbon tariffs or other international regulatory barriers forcing us into action.

For others “responding” will mean doing all we can to not damage the planet in the first place - by reducing New Zealand’s net emissions and pushing other countries to do the same.

In other words, the way you ask the questions is key. And that is a big part ofthe difference between these two agencies’ briefings. MPI asked a very narrow question: What will this mean for global food demand, and got an answer that is applicable to New Zealand export revenue but not New Zealand as a whole. MfE asked a wider question about “ensuring the future wellbeing of land and people” and got a very different answer.

It is for ministers to ask these questions, and decide which of their ministries have answered them better. But the range of acceptable answers will be decided by the people writing these reports. We should pay attention to how they think.

Recommended reading:

FT: small caged mammal.

Sam Friedman on the use and misuse of issue-based polling.

Audrey Young’s profile of Chris Hipkins.

Vernon Small on the state of the polls.

Jo Moir on Kiri Allan.

Is milk a protein, I hear you asking. The dairy industry generally seem to get subsumed into discussions about the wider protein industry, so I would argue yes.

This may well be a deliberate decision of ministers. All Government departments have built in ideological frameworks, and ministers get to know these pretty fast.

A good read and thanks for doing what most of us don't; go through documents from our Govt departments and comparing them. I was at a AFRA (Aotearoa Food Rescue Alliance) press conference where they released a manifesto for political parties to sign up too, calling for A National Food Plan and mandatory reporting of food loss and value across the food chain. The amount of food waste is apparently a huge carbon waste for our little country. But one statement that you hear thrown about a lot is that "we produce enough food to feed 40 million people". I am not sure that's really true given that much of our dairy product is exported in the form of milk powder and I believe that product largely goes into confectionary products and that's hardly feeding 40 million in a viable way. But I do think many people are cutting back on meat and dairy... those products are very expensive in our supermarkets but also I think people are also thinking of the cost to our waterways and our reputation abroad. We are hardly clean and green are we? Given how many climate events we are seeing across the world, I do think we absolutely have to put climate first and to feed our own first, rather than gather more export dollars. It's a tricky balance but without habitat we are nothing.

Really nice summary of both department's reports.

What I find interesting is that while the MfE report does mention it, neither report really understands the impact of modern biology on our agricultural sector.

There are already companies making dairy products using precision fermentation (eg Perfect Day). In other words we should in the next decade see most if not all of the purified milk proteins being produced in fermentation tanks. That should make them cheaper and almost certainly make them less harmful to the environment and less dependent on the environment. It is worth noting that Fonterra makes a big chunk of it's profit from those purified milk proteins. I don't know whether milk as we know it will be produced in fermentation tanks but if it is then on both price and environmental grounds a lot of people will be keen to switch to it. How both government departments can ignore that potential is surprising.

The outlook for meat is no better, while it's true that replacing a quality piece of beef or lamb (not to ignore chicken and fish) is going to be a hard task, we already have replacements for minced meat. And yes while those are more expensive both in dollar terms and in resources at the moment I would not want to bet that those costs don't come down. What that might mean is that the market for bulk meat (eg mince, burgers, sausages etc) could collapse. That in turn means that the premium cuts need to pay the entire cost of raising the animal. The maths on that will be tricky but I wouldn't be surprised to see premium cuts double or triple in price at the same time as mince substitutes halve. And like with milk many consumers will consider both cost AND environmental harm when choosing plant- or fermentation-based mince substitutes.

The impact of climate of trends like these is simply that much of the dairy and meat substitutes are relatively resistant to climate changes. That resilience is going to become much more significant over the next couple of decades.

Unless New Zealand is part of the change that is coming I can't see any good outlook for our primary industries.