A tale of two memoirs

Some notes on Ardernism, plus a little bit of professional news.

Hello from Cyprus, a country divided into three different sovereignties : British-controlled military bases only kept alive with US funding, the disputed northern area only recognised by Turkey, and the larger Greek republic recognised by everyone else.

I’m here on holiday but one can’t help but be reminded in a place like this of just how uncomplicated little old New Zealand is. Cyprus too is a small former British colony a long way from the UK - but its journey to independence has been about as different as you can possibly imagine.

It’s also been a reminder of how even extraordinary political situations often become normalised over time, as the abject and unusual become everyday status quo. We passed over into Northern Cyprus with our passports the other day in Nicosia, into a disputed state over a “green line” that has been controlled by the UN for decades, and it felt like getting carded on your way into a club: Easy, routine, boring for everyone involved. After long enough people just find ways to work with this stuff, whether it be the 71-year-old temporary ceasefire in Korea or the enclave of West Berlin surrounded by the East.

Yet this status quo hides latent tensions which build up during these extraordinary/ordinary times. Eventually the Berlin Wall came down. For decades it was the fact on the ground that seemed impossible to displace - then with a few words in a press conference it was gone.

Jacinda Ardern governed through some truly extraordinary times. There was no disputed international borders, but there was a border placed on Auckland, complete with police checkpoints, something almost impossible to imagine in 2019. For a while all these emergency measures seemed, while not quite normal, not entirely alien either. They mostly polled extraordinarily well. But behind it all there was a latent tension building up - one that would explode onto Parliament in early 2022, and still fills some Kiwis with rage.

I’ve been thinking about Ardern lately as I was lucky enough to get an advance copy of her book - which I reviewed in The Listener. Long story short I think it is worth your time, as it does give you some insight into her mind during some extraordinary crises, and given Jenny Shipley, Helen Clark, John Key, and Bill English have all refused to write memoirs we should be somewhat happy with any PM that does. It is also deeply frustrating in how much it elides, in how much it doesn’t confront. There is not a true reckoning with how the pandemic response eventually became more and more arbitrary, or the way it radicalised a sizeable minority of the public. There is very little on her really thinking through how much of her project has been undone in swift succession by the new National Government, a fate that did not befall the achievements of the Fifth Labour Government.

In the review, I offered a small thesis on what exactly “Ardernism” was, this “Different Kind of Power” promised in the title.

This intimacy is crucial to the wider point Ardern is trying to make in the book: that she wants people to know they can be politicians while still doubting themselves, can be humans first and politicians second, and that indeed the first job will make them better at the second job. This is the closest thing to a one-sentence summation of Ardernism she ever really offers.

Ardernism was always more a sensibility than an ideology. It was a way of looking at the world and reacting to it, not a theory of change. It was being good in a crisis – and she really was. Reading about those fraught days in March of 2019 and 2020 again from her perspective is clarifying. Ardern was able to reach into a reserve of something in those two horrible months that few of our leaders ever have, a kind of pure political power that transcended the office and represented exactly what Kiwis like about our country, not just empathy and warmth but an organised resolve.

I think it is fair to say that Ardern’s ability to seem like a normal millennial women was a huge part of both her appeal for many and her repulsiveness for others. It was easy to see yourself in her - or see someone grossly unqualified for the job, someone who was always talking about her personal life1 and not the real business of governing. To be fair, any prime minister will suffer some degree of horrible personal attacks, and it seems women of any stripe get the worst of it. But it is also fair to say that Ardern being so clearly the driving force of the Government with her daily press conferences meant it was inevitable that principled attacks on the Government’s position often include serious criticism of her as a person. She was not a leading soldier in Labour’s army - she was Labour. Her departure and the party’s idling in neutral ever since make this more clear than ever.

And as the personal embodiment of New Zealand’s oldest political party she did not appear to have what it took to drive lasting change. Some of her legacy does remain - Best Start exists in some form, abortion is legalised, the Winter Energy Payments are still there, and the Zero Carbon Act is the law of the land. But there is a reason she spends so much of the book on her responses to crises: they will be what she is remembered for - both here and abroad.

It is the “abroad” part that leaves a bit of a bad taste in the mouth. The book is understandably written for a foreign audience - she translates “waka” and talks about being in her “junior year” of high school. Ardern did glitzy sitdown interviews with foreign media but relatively few with anyone in New Zealand. And when I wrote the review there was no book tour dates announced for New Zealand, although her people assure me she will be visiting.

While it is commercially absolutely understandable for Ardern to write for Americans and Brits inspired by her, it is frustrating in how much it clearly holds her back from really getting into the nitty gritty of some of the policy debates.

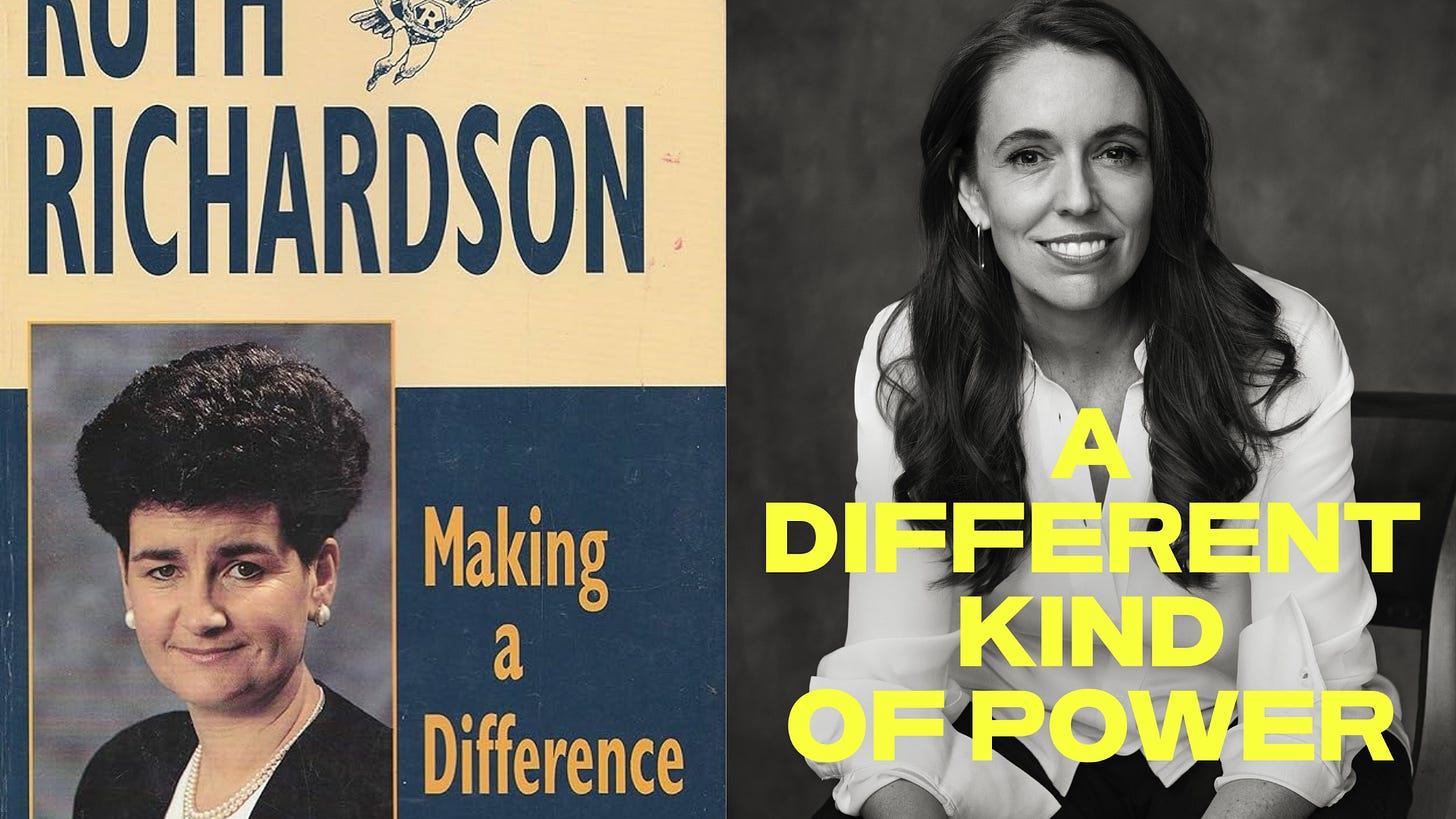

Perhaps it suffered because I read it just after another political memoir: Making A Difference by Ruth Richardson.

Richardson's book was also written a few years after she left power. But unlike Ardern she is very keen to put down the exact detail of many policy debates she was involved in, debates that still shape the country now, and offer a robust defence of them. She is keen to talk about how she changed the country, how she was stopped from changing it more by the timidity of her colleagues, and how she worked to embed that change in stone with the Fiscal Responsibility Act. Indeed, she prints the entire bill at the end of the book.

Ardern and Richardson are diametrically opposed politicians - but both were at some points in their life eager to seriously change the country. Richardson managed to, and spends her book explaining exactly how. It’s not quite clear yet if Ardern ever did.

Some professional news

Ardern’s legacy is not a topic that I am done writing about, but I am short on time and have some professional news I wanted to share here: I will be returning to Parliament in September to take up the role of deputy political reporter at The Post.

I am very excited to be a full-time political reporter again. I’ve been working in PR full-time in London for the last three years, and as you can probably tell from the fact that this newsletter exists, missing reporting a lot. I worked at Stuff for a decade before leaving for the UK so it feels a lot like returning to my home two times over.

What will it mean for this newsletter? Obviously once I start at The Post I will doing my full-time reporting and analysing and what not for them - so if you enjoy my work, do consider a subscription. But every now and then I’m sure I will have some topic far too esoteric or piece too long-winded to really make sense there, so do expect pieces from time to time. This newsletter has been far too much fun for me to simply drop now that I have a job again.

And until September, I’m running around Europe doing a bit of a freelancing and a bit of holidaying. So I’m sure we will talk many times before then. Thanks as ever for reading and subscribing - it really has been so much fun connecting with the readers of this newsletter, who engage properly with the content rather than just getting angry at the headline2. You are far too good of an audience to throw away, so I am sorry that I have written so rarely. Yamas!

It’s probably worth noting that she was not always so keen to share details of her personal life with the media, but the thirst for details from both domestic and international media was insatiable. The book makes clear how much personal detail - from a cancer scare to serious nausea at the state opening of Parliament - she was keeping away from us.

It helps that I use such boring ones.

Welcome home!

I think it’s impossible to say Ardern didn’t change the country, as she shaped it *while* it was changing. It’s just that she perhaps didn’t change it through her legislative agenda as Richardson did. But I don’t think it’s a bad thing that it’s hard to summarise ‘ardernism’, or to label it. It shares its uncertainty with the entire leftist movement — and like leftism, it’ll get there. Give it time.

Better people question Ardern’s legacy than immediately settle on something like “Ruthenasia”. I was surprised to learn Richardson was proud of that. I imagine Ardern would be horrified if her legacy was such — ironic, as Ardern actually legalised euthanasia.

I think what Ardern did was not legislative but bureaucratic and executive-lead. And it was demonstrative. Not to be too personal but I’m at the mercy of the system currently and something notable I experienced was that WINZ became

so friendly, some people forgot that they ever could be awful. Not me. But Ardern made the country hopeful and pushed us towards a better tomorrow, made us think that tomorrow was today, and her takeover from National made it seem smooth enough that people forgot what NACT are like.

It felt like the changes she had made at the time were irreversible because what she changed was the culture, the focus, the *how* — the social safety net was made safe. No more holes. Make it out of soft, not razor thin wire that cuts you when you ask for help. Ministries like Whaikaha tested and expanded Enabling Good Lives-like support across the entire country. Maori were being acknowledged as partners, if perhaps not entirely treated as one. But she unified and typified the sort of progressiveness that New Zealand prides itself on.

Some of it even NACT can’t go back on openly, like EGL philosophy under Ministry for Disabilities, though they’ll certainly cut it to shreds in their attempts through bad budgeting and by removing its main financial function and giving it back to the only government department to ever inspire a mass shooting.

I cannot emphasise enough the incredible turnaround that happened there — someone shot up a WINZ office because WINZ was so awful, and then a short time later, support organisations had forgotten that WINZ could be terrible and turned hostile.

But it at least pushes the right’s ideology more firmly into a space where it must operate more openly, and its hypocrisy and repetitiveness becomes more visible. They are anti-kindness, anti-support, anti-progress. They are the third right-wing austerity government of three — and like the Tories eventually did in the UK, they’ve run out of believable excuses. It’s apparent that it’s austerity for the sake of austerity. It’s self-made austerity too, pure ideology pushing for privatisation and taking money out of the economy, causing all manner of catastrophes NACT now have to pretend to fix, in which their economic management merges with social stances to reveal the deep classist and corrupt roots that permeate the “center” party and its pet attack dog.

I think Ardern’s legacy has to be the response to *her*, and what she showed us our responses can be. She said the word out loud — empathy. Kindness. Openness. She showed us radicalism was wanted and needed, that the country was ready for change: that we thought we were changing, even, transforming into a more unified and stronger nation through our crises. We were setting examples internationally. When really, we weren’t.

But the reactionary response has exposed the deep divisions that pervade politics and prevent us from moving forwards. We are in a six-to-nine year cycle of funding and defunding in an exhausting endurance test where the right are still pushing their extreme unwanted legislative agenda from the 2000s and the 90s on to an unwilling, barely-noticing nation, and the lack of responsible management and the consequences of chopping and changing and underfunding things that are politically unpopular to pay for in a post-neoliberal society are very apparent.

Ardernism and its legacy is, I think, whatever we do next.

I often wonder why no-one holds Ms. Ardern to account for the destruction she wrought on Kiwi women and our rights by supporting passage of the Self-Id provisions of the BDMRR Act (2021) and the act prohibiting counselling for gender-confused children (the conversion practices ban - an exercise in Orwellian double-speak). Those of us who begged her not to legitimise medicalising children who don't fit sex role stereotypes lost. But women and men in NZ lost big time when biologically-based legal categories for "woman" and "man" were scrapped by her. And because biology does matter, women are - as usual - the bigger losers. It is poor consolation that those opposing these measures have been more than fully vindicated by reviews of paediatric medicine for such children in Finland, Sweden, the UK and the US, to name a few. If you, Henry, were previously on the staff of Stuff, there is presumably little chance that you would wish to examine these issues for yourself. For Kiwis who are interested in what this all means, Broadsheet, New Zealand's Feminist Magazine continues to promote an understanding of these issues on its Facebook page.