Who are the ACT Party base?

A deep dive into the supporters that rocketed ACT back into political relevance, with far too many graphs.

In November of 2019, David Seymour stood in Parliament to shepherd through what he probably expected to be his political legacy.

The End of Life Choice bill had taken over the ACT leader’s life since being pulled from the ballot in 2017. He and his indefatigable staffer Brooke van Velden spent hours upon hours building a coalition inside and outside Parliament that would get the bill through its two-year legislative process. Seymour had serious enemies to go up against - notably the Catholic Church, the New Zealand Medical Association, and Nick Smith - but he won.

Despite this quite serious victory, ACT itself was failing to find much support. Polls put it at between one and two per cent of the party vote - not much higher than the 0.5% it had managed in the 2017 election. ACT had not won more than a single seat in any election that decade, and it looked very likely that it would not do so any time soon, remaining as a bit of an electoral oddity that clung on to political life with its fingertips thanks to Epsom.

Just four short years later, ACT are ascendent.

If National win the election later this year, the Government it forms will be more reliant on ACT than John Key or Bill English ever were on any other party. ACT MPs will likely make up close to a third of this potential Government’s coalition, meaning they will very reasonably be able to argue for a suite of high-impact cabinet portfolios and quite a bit of control over the direction of Government policy1.

This resurgence of ACT is a relatively recent phenomenon, and one worth exploring in depth. The party won 16 times more votes in 2020 than in 2017, jumping from a measly 13,000 party votes to 219,000 in its strongest performance ever. You could argue that this historic result was largely based on National’s weakness, but ACT managed to keep the support at this high water mark and grow it, even as National got its act together following the election. ACT now continually polls at or over 10%.

This post takes a look at who these new ACT voters are, using the trusty old New Zealand Election Survey (NZES) results from 2020, much in the vein of my earlier post on Labour’s lost voters. This survey of thousands of voters taken soon after every election is the best political resource we have for understanding what NZ voters actually think2. Let’s get started.

The typical ACT voter: A 49-year-old straight white male

We will start with some demographic indicators before we dig into political views.

(As a methodological note for those interested, whenever I refer to “ACT voters” from here on out I mean those who party voted ACT in 2020 and told the NZES about it3. I will be comparing them both to the entire dataset (which includes non-voters) and voters from other parties.)

The median birth year for ACT voters is 1974, making them 49 this year. The typical ACT voter is about three years older than the typical elector4, who was born in 1977.

The ACT voter is not dramatically older than the general population. The median NZ First voter, for comparison, was born in 1965, a full 12 years ahead of the median elector, and the median Green Party voter was born in 1989, a full 12 years after the median elector. This doesn’t mean ACT’s support doesn’t skew a bit old, but it’s not all that dramatic. Here’s another look at the age distribution of party support.

As you can see, ACT aren’t all that far away from the age distribution of the total electorate. Meanwhile the Greens are incredibly reliant on young voters.

But age is just one number. We are interested in lots of numbers.

On ethnicity, 90% of ACT voters said they were European, compared to 78% of total electors. You can say with confidence that ACT voters are more likely to be white than the typical voter, although the typical voter is white in general. On a related note, 88% of ACT voters said they were born in New Zealand, compared to 80% of electors.

On gender, 66% of ACT voters were men, compared to 48% of total electors.

On sexuality, ACT are again with the majority, only more so. 94% of ACT voters said they were “straight” while 3% said they were gay, lesbian, or bi. (Some declined to answer.) In the general electorate 84% said they were straight and 7% said they were gay, lesbian, or bi.

This continues into marriage - 78% of ACT voters said they were married, compared to 60% of the general electorate.

Next let’s look at where these voters live.

As you might expect, ACT voters are more likely to live in rural areas than the typical New Zealander, with a majority living in either a rural area or a small or middle-sized town. That doesn’t mean there are no ACT voters in big cities, but it does mean they skew more rural than the general electorate does.

In many other countries, the big split between left and right is predicated as much on education as anything else, with the university educated going left and those without university education going right. You can see a little bit of that in New Zealand too. 15% of ACT voters have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 27% the general electorate. As with age, the difference to the left is stronger than to the right - a huge 55% of Green voters have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Next up let’s look at economic factors.

As you can see, ACT voters generally live in households with higher income than the general electorate. But the difference isn’t all that stark - it might surprise you to know that a higher proportion of Green Party voters live in households that bring in $149k+ than ACT voters.

On home ownership, ACT supporters are once more with the majority only more so: 68% own their own home, compared to 63% of the general electorate. This difference is fairly small - as a comparison 80% of National voters said they owned their own home, making that party more squarely the political home for home owners.

National again beat out ACT when it comes to investment properties or baches. 33% of National voters said they owned a bach or investment property, compared to 27% of ACT voters and 19% of the general electorate.

Let’s look at what these voters say they care about.

How ACT voters see the issues - the culture war

I don’t mean to alarm you, but ACT voters generally consider themselves to be right-wing.

You can see this in the above chart. Most ACT voters place themselves on the right of the political spectrum. They are more likely to see themselves as right-wing than the general elector (who is most likely to say “don’t know”.) Perhaps surprisingly for a party seen as “to the right” of National, ACT voters actually place themselves closer to the centre than National voters.

Why might this be?

One potential factor is social issues. ACT in the 2017-20 term was highly associated with generally liberal social views - Seymour was pushing for End of Life Choice and voted to legalise abortion. The newer social policy issue of trans rights had not gained as much salience at this point as it would in the 2020-2023 term.

And if you look at traditional social issues like abortion, ACT’s 2020 voters were generally fairly liberal - as was the country as a whole.

Just 5% of ACT voters strongly agreed with the statement “abortion is always wrong” - compared to 11% of the general electorate and 13% of National voters. On euthanasia 80% of ACT voters said they had voted “yes” in the referendum compared to 60% of National voters.

But on other social/culture issues ACT voters did veer a bit more right. Roughly the same proportion of ACT and National voters (24% and 25%) strongly agreed that the death penalty should be brought back - a view shared by 21% of the wider electorate.

Seymour got a lot of attention when he opposed the gun law changes made after the Christchurch terror attack in 2019. It’s easy to assume this won him a big batch of gun-focused voters right away, but it’s worth noting his party’s polling didn’t really shift at this point. And while ACT voters were slightly likely to say they were “disgusted” by the response to March 15 than the general voter, this was still an extreme minority view: Only 5% of ACT voters said they were disgusted by the response, compared to 2% of the general population.

When we get to Māori issues a bigger divergence between ACT voters and the general population emerges.

As you can see here, it’s hardly a minority view that the treaty process has gone “too far” or “far enough”. A majority of the electorate feel that way. But ACT voters are far more likely to agree with that - and dramatically less likely to think the Treaty process has a longer way to go.

This extends out into other questions about the role of Māori in Government decision-making and the Treaty. ACT voters are almost twice as likely to want “references to the Treaty removed from the law” than the general population - 41% to 23%. When asked if it is important for being a “true New Zealander” to speak te reo Māori, 90% of ACT voters say it is “not very important” or “not important at all” - compared to 72% of the general electorate.

None of this should be particularly surprising to those who have followed ACT’s rise over the last four years. Seymour went very hard against the Ihumātao protestors in the 2017-2020 term and was ahead of National on the fight over ‘co-governance’. His party have raised treaty issues back to political salience after the National Party in Government largely depoliticised them, and ACT are now clearly defined as the party “against” co-governance and the like, a position NZ First are desperately trying to reclaim. National have jumped on this issue too - particularly when Collins was in charge - but as a smaller party which didn’t enact co-governance initiatives when in charge a few years ago, ACT have the ability to go further faster on this issue.

ACT voters are also to the right on other issues to do with the intersection of race and culture, but not as dramatically. 29% of ACT voters either strongly or somewhat agreed with the phrase “New Zealand culture is generally harmed by immigrants” compared to 20% of the general electorate. A majority of both ACT voters and the general public disagreed with this sentiment.

And finally one more issue you can kind of put in the culture bucket - climate.

ACT flirted with full-on climate denialism back in the day. It seems some of the voters who retain skepticism have stayed with ACT - but they also support National. While a majority of voters for both National and ACT agree that climate change is “caused by humans,” (58% for National and 59% for ACT) each party has a significant minority which believes it is “happening naturally” (32% for National and 33% of ACT).

The Ardern factor

Before we get into economic issues, a brief word about Jacinda Ardern, who was prime minister at the 2020 election.

ACT voters were far and away more likely to dislike Ardern than both National voters and the general electorate. 17.3% gave her the worst possible rating - a 0 out of 10 - compared to 6% of the general electorate and 11% of National voters.

Now, it isn’t that surprising that voters for an opposition party would dislike the current prime minister. I’m sure you would see similar figures for Green Party voters when asked about John Key in 2017. But given just how much air time Ardern had in 2020, it’s worth a quick look.

Time to get into spending.

How ACT voters see the issues - the economy and spending

ACT grew out of the economic right-wing of the Labour Party joined up with some of the economic ultras in National. The party has generally branded itself as being economically libertarian: Interested in a state that taxes and spends less.

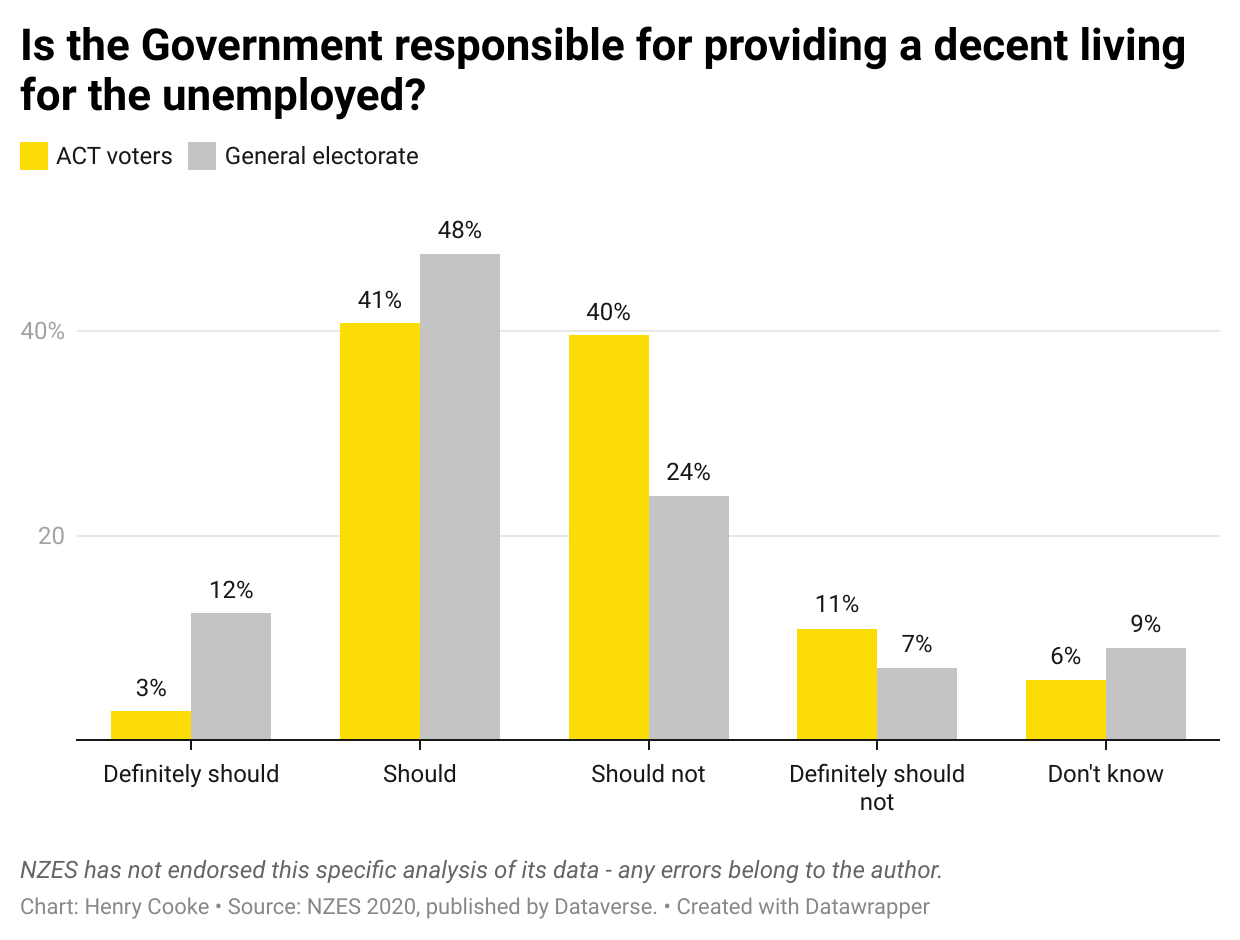

At first glance, the party's voters seem to agree, particularly when it comes to spending on the unemployed.

On the general philosophical question over whether the Government should provide the unemployed a decent living, a majority of ACT voters say the Government shoudn’t. A similar majority of ACT voters (54%) said the Government should spend less on unemployment benefits, compared to 33% of the general electorate.

This difference can also be seen on questions about tax and debt.

This question about economic debt is framed in a way that some would take issues with, but you can still see that ACT voters are more likely to push for debt reduction than the general electorate - although very few are real ultras about it.

This question about hypothetically cutting taxes to help the economy shows again that ACT voters are typically to the right on big picture taxes and spending.

But as with many voters, once you start asking about where they want to cut spending things get a bit dicier. After all the jobseeker benefit only makes up about 2.7% of core crown spending - a lot less than spending on superannuation, health, and education. And yet:

Just 11% of ACT voters supported reducing public spending on superannuation - compared to 7% of the general electorate.

Just 3% of ACT voters said supported reducing public spending on education - the same proportion as the general electorate.

Just 2% of ACT voters supported reducing public spending on health - compared to 3% of the general electorate.

Indeed, a majority of ACT voters actually wanted more spending on education and health.

ACT voters are far from alone here. A lot of Kiwi voters want both low taxes and high public spending on services. But it does go a way to explaining why Seymour has found so much more success focusing on culture issues over economic ones.

There are many more takes one could have on all this data, but this piece is long enough already. For now adieu. I am sorry it has been so long since the last post.

Of course, much like the Greens, ACT have nowhere to go if National say “no” - save from the crossbenches. But that doesn’t mean the party can’t extract significant concessions through threats to publicise disagreements and the like.

Or at least, how they did think. The survey obviously captures people who voted ACT in 2020 - not the larger group of people who say they support the party now. But you work with what you have, and I think it is a reasonable assumption that most of those who voted ACT in 2020 are still with the party.

The results are all weighted to make them as representative as possible, and I’m using validated party votes. I’ve rounded to whole numbers.

I say “elector” because the survey includes non-voters, although at some points I will slip and just say “typical voter” because “elector” is an awkward word. I don’t just say “Kiwi” because the survey does not include those not eligible to vote - ie anyone younger than 18 in 2020.

Jeez I am the exact demographic, except I have a degree and am opposed to just about everything that comes out of the smug prick’s mouth.

That was a fascinating read, many thanks Henry